Photo: Mark Peterson/Redux for New York Magazine

This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

The center of the center of bitcoin in the physical realm, one could argue, is a run-down two-story house on Leverett Street in the small New Hampshire town of Keene. Half-covered in peeling green paint, it’s got a wraparound porch crammed with rotting sofas, a satellite dish, bug-zapping devices, and some potted flowers. If billionaires have a scent, it is not the one you smell inside — a rainy-season Granite State musk of earth, sweat, and gorp.

On the last Sunday in May, ten days after posting a $200,000 bond and getting out of jail, the house’s primary occupant, Ian Freeman, sits down in a recording studio on the first floor to host an episode of “Free Talk Live,” the radio call-in show he founded two decades ago. At 41, dressed in a softball shirt, blue jeans, and an ankle monitor, he resembles Novak Djokovic, with short black hair, skeletal features, and the complexion of a white paper. The show begins, as it does seven nights a week, with a barrage of churning guitars — in contrast to Freeman himself, a serene presence who describes his life’s work as “advocating for peace.”

Although he was one of the first Americans to popularize bitcoin, ten years and several million percentage points of investment return ago, Freeman has been hawking cryptocurrency less for the money and more for the libertarian ideals he believes it represents. Here in rural New Hampshire, he has long been the figurehead of an activist collective called Free Keene, which agitates against state power in every form, from cops to taxes. He is also the co-founder of an upstart parish called the Shire Free Church, devoted to weaning his rural enclave off government money. Thanks to his efforts, Keene has credibly been called the per capita crypto mecca of the country, but Freeman’s zealous prioritizing of bitcoin’s on-the-ground social potential over its financial power has cost him. Forbes tracks 12 cryptobillionaires on its list of the world’s largest fortunes; Freeman lives on Leverett Street with his girlfriend, Bonnie Kruse, and a revolving cast of roommates, the latest of whom is a gun enthusiast named Matt who sells pet insurance.

Matt is shirtless and playing video games in his room as Freeman begins his broadcast, joined by two of his regular co-hosts: a metal-band guitarist who goes by the Rev. Captain Kickass and a massage therapist whose nom de crypto is Peakless Mountaineer. All three present as curious and hyperarticulate, if dogmatic in their politics, which verge on the anarchic. Tonight, they’re discussing nonfungible tokens, the cryptographic watermarks that have conferred a staggering degree of value on seemingly worthless digital images. Freeman is skeptical. He mentions the forgotten Cryptokitty fad of 2017, in which people transacted NFTs of virtual cats. “People seem to be kind of split on whether they’re a good idea or not, and I say more power to ’em,” he says placidly. “Personally, I have no attraction whatsoever.”

Peakless Mountaineer, though, wonders if NFTs could augur a golden age of decentralized record-keeping. “The very word register — like, to register a thing — I mean, the root is king,” he says. (The etymology is disputed.) “You are giving it to the king’s men so that they will keep track that you registered this piece of land or whatever it was. And we don’t need the king to register things now.”

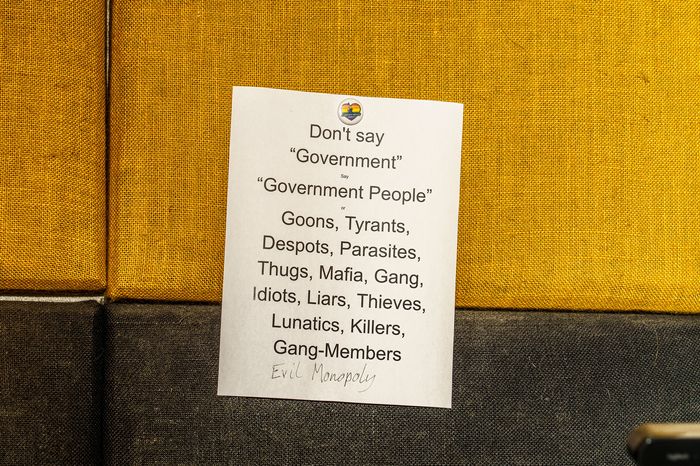

Soon a caller from Texas asks Freeman whether holding someone in jail before being convicted of a crime violates the 13th Amendment and might be, technically, slavery. This is the kind of thing people talk about every night on “Free Talk Live,” which the radio-industry bible Talkers rates as the 25th-most-influential program in the country, six spots after Ben Shapiro. On the walls of the studio, Freeman has tacked up lists of preferred synonyms for government, including goons, tyrants, despots, parasites, thugs, mafia, idiots, liars, thieves, lunatics, killers, and gang members. “Well, we’re all already slaves,” Freeman tells the caller. In his view, anybody subject to government laws is chattel. Captain Kickass counters, “You are more of a slave right this moment than I am,” and Freeman readily concedes the point.

Two months earlier, on the frigid early morning of March 16, two armored BearCats rolled up to Freeman’s house. Camo-clad federal agents spilled out, busted a window, and flew in a drone to make sure no one inside had a rifle or a suicide vest; then they stormed in, upending the studio, seizing computers, handcuffing people, and hauling Freeman away. In and around Keene, authorities also raided the homes of five of his associates. Later that day, in Concord, New Hampshire, Department of Justice prosecutors unveiled a 20-count indictment against them, the culmination of a five-year investigation.

The government alleged that Freeman had been running a sophisticated multimillion-dollar racket that enabled “hordes of cyber criminals” to scam victims and launder money. To do this, prosecutors said, Freeman and his crew used both online accounts and crypto vending machines to execute thousands of unlicensed transactions, trading the Shire’s bitcoin for cash without asking too many questions about its origins. Freeman was also charged with enlisting friends to stash his operation’s proceeds into newly created bank accounts under false pretenses. (Freeman and his codefendants have pleaded not guilty.)

During the raids, agents seized more than $200,000 in cash as well as two novelty physical bitcoins embedded with the digital coordinates to what was then worth about $5.7 million. As for how much crypto Freeman or the Shire Free Church has socked away in digital wallets — well, the whole point of bitcoin is that the government has no idea. When I visited Keene, one well-connected member of the Shire told me that the church’s bitcoin reserves are in the four figures, which would translate to $50 million or more.

Impressive as that would be, the dollar amount isn’t what is significant about what is alleged to have transpired in Keene. (In May, the Securities and Exchange Commission sued five people for their involvement in a scheme measuring 40 times larger.) Freeman and his crunchy partners represent bitcoin’s founding politics — its anti-state origins, which have been all but forgotten thanks to the asset class’s vertiginous price swings; its overnight minting of a new and poorly understood set of billionaires; and sideshow manias like the one for NFTs. That side of bitcoin is all over CNBC. In the antigovernment enclaves of New Hampshire, though, Freeman and his co-defendants have become a cause célèbre, martyrs dubbed the Crypto Six. Libertarians have rallied to their defense, printing T-shirts, establishing a legal fund, and picking apart the government’s case. “It sounds like he is guilty of free trade,” says Erik Voorhees, a pioneering crypto investor who used to run in the same New Hampshire circles.

Freeman’s plight has also generated Schadenfreude among the ordinary Keeners who see his movement as a blemish on their tidy town, population 23,000. Freeman & Co. have been pulling bush-league civil-disobedience stunts for years, paying property taxes in stacks of $1 bills and serially harassing meter maids. (That undertaking was absurd enough to merit coverage on The Colbert Report.) Freeman’s co-defendants include someone legally named Nobody, as well as Aria DiMezzo, a self-identified “transsexual Satanist anarchist” who last year ran for county sheriff on a “Fuck the Police” platform. Lately, the antics have gotten more perilous. When COVID-19 lockdowns hit, Freeman’s crew protested mask mandates and organized unsanctioned indoor gatherings, including a rave. For average New Hampshirites — those who don’t know Satoshi Nakamoto from John Sununu — all this fuss about bitcoin is a smoke screen for people who just want to troll the government.

As Freeman sees it, the two ideas are inseparable: Using bitcoin is provoking the government. Supplanting the dollar and weakening the central banks that print fiat notes with abandon: This was the shared vision of bitcoin’s founding generation of investors and evangelists, a cohort that included a significant number of “Free Talk Live” listeners. And this vision, Freeman reasons, was threatening enough to the government that it freaked out and threw him in jail. “For the first time in generations, if not most of human history, the individual can finally have control over money,” he says. “No wonder they’re upset.” The ultimate target, in other words, wasn’t Freeman or the Shire but cryptocurrency itself. His defenders portray his ascetic lifestyle as exculpatory, proof that he isn’t trying to line his own pockets — however much digital gold may be secreted in church coffers. “You’ve seen how he lives,” says Mark “Edge” Edgington, who co-founded “Free Talk Live.” “He could have moved anywhere in the world. He could have had women, and pools, and drinking. He could have had whatever lavish lifestyle you can imagine.”

At one point during “Free Talk Live,” a caller from Los Angeles asks Freeman if he’d have done anything differently had he known he would be indicted. “Is there something I regret? I mean, of course not,” he says. “This is my mission. I’ve been given this mission from God to get this alternative form of value into people’s hands.”

Ian Freeman and Bonnie Kruse on their porch.

Photo: Mark Peterson/Redux for New York Magazine

Ian Freeman, born Ian Bernard, was raised on the Gulf Coast of Florida on an information diet of Rush Limbaugh and DARE. He veered libertarian at 16 after his first toke of pot. “It wasn’t this terrifying, horrible thing,” he says. “It made me wonder what else the government was lying to me about. And it turns out it was almost everything.” He studied radio and television at Manatee County Community College, an experience he calls a “total waste,” but his interest in broadcasting led him to a fill-in DJ job at a rock station in Sarasota. There, in 1999, he met Edgington, a co-worker who had been convicted of second-degree murder and spent eight years in prison, where he started turning against the state, carceral and otherwise. (While on drugs in a seedy motel, Edgington says, he unwittingly helped kill someone he thought was attacking his friend.) Together they started “Free Talk Live.”

Around this time, a Yale Ph.D. student named Jason Sorens was founding the Free State Project — an effort to get 20,000 libertarians to move to a small state and start swinging votes. Sorens landed on New Hampshire for its pro-gun, low-tax sensibilities as well as for its chaotic legislature, which pays a salary of $100 and elects all kinds of eccentrics. (To date, more than 5,000 Free Staters have migrated there.) Ian Bernard and Edgington joined the movement and in 2006 took themselves and their radio show to Keene.

Even by the standards of the Free State Project, the ecosystem that germinated around “Free Talk Live” was out there. On the streets of Keene, Freeman — as he began calling himself — set the tone by flouting minor ordinances and then representing himself in court, causing maximal inconvenience to local officials. He fought the city for trying to remove furniture from his lawn and once was sentenced to 90 days in jail for obstructing a police car. A Mother Jones reporter described his activism as a “hybrid of Gandhi and Project Mayhem,” the terrorist cell from Fight Club.

Other transplants in town followed suit, and their antics came to be described as the Free Keene movement. One of Freeman’s roommates, Derrick J. Horton, filmed a documentary about his own “victimless crime spree” of minor offenses, which landed him in jail. Another Keener, Christopher Cantwell, went around stuffing coins into soon-to-expire parking meters to deny the town ticket revenue. (Cantwell would later embrace white-supremacist “statism,” gaining meme infamy as the “crying Nazi” of the 2017 rally in Charlottesville, Virginia.)

By 2010, Freeman and his fellow travelers were seeking to channel the Free Keene ethos into something grander — an entity called the Shire Society. It wasn’t a membership organization, exactly; the people arriving in Keene weren’t the type to adhere to bylaws. But it served as an umbrella for the movement, with an internet presence of chat forums and spinoff websites. The Shire was a paradox: a tight-knit community devoted to decentralization with a righteous leader in Ian Freeman. It became a haven for outsiders and misfits of all kinds, including those interested in subverting the dollar.

In January 2011, Gavin Andresen, a Princeton-educated software engineer and fan of “Free Talk Live,” emailed Freeman and Edgington to ask if he could buy them lunch. In his spare time, Andresen was the lead developer of a fledgling digital project known as bitcoin. Three years after the currency’s invention, few were paying attention, and Andresen was literally giving away coins online. At a Thai restaurant, Andresen pitched Freeman and Edgington on the concept, hoping they might give it airtime. Freeman didn’t really get it. Plenty of libertarians had tried to create peer-to-peer currencies before, including one in their backyard called Shire Silver; how could bitcoin have any value if it wasn’t backed by something like a precious metal? Andresen returned home, sending 46 bitcoin ($2.2 million in today’s money) to cover his meal.

A few months later, though, Freeman discovered the black-market site Silk Road and everything clicked. Here was a thriving marketplace where users transacted anonymously and seamlessly thanks to the magic of cryptography. The merchandise was mostly drugs and contraband, sure, but the point was that the government couldn’t meddle — a true free market. Freeman gushed about Silk Road on that night’s episode of “Free Talk Live.” Listening was Roger Ver, a Tokyo-based “free-market anarchist” who had once served time in prison for selling unlicensed explosives on eBay. Ver was a patron of the show, contributing $3,500 each month to keep it on the air, and he asked the hosts if he could start paying them partly in crypto. This time, Freeman was in.

Ver would go on to become a crypto legend: He backed the seminal bitcoin exchanges Mt. Gox and BitInstant, which became one of the first crypto investments of Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss. They became billionaires; Ver became known as “Bitcoin Jesus.” Freeman, evangelizing crypto in its dirt-cheap infancy, could have followed in Ver’s footsteps and amassed a fortune. Instead, he stuck around Keene to fight for his cause. And in retrospect, maybe Freeman is the one they should have called Bitcoin Jesus. “He’s got a savior complex,” Edgington says. “If he finds a cross, he’ll nail himself to it.”

Every so often, a new place is anointed the real-world capital of crypto, but none has truly stuck. After a hurricane devastated Puerto Rico in 2017, digital speculators moved to the island and vowed to rebuild it; today, Crypto Rico seems like a glorified tax shelter revolving around the entourage of a former Mighty Ducks actor. San Francisco had its Crypto Castle, and Miami courts the industry with investor bacchanals, but in both cities, overwhelmingly, the point is to make a balance-sheet killing, not to truly live on the blockchain.

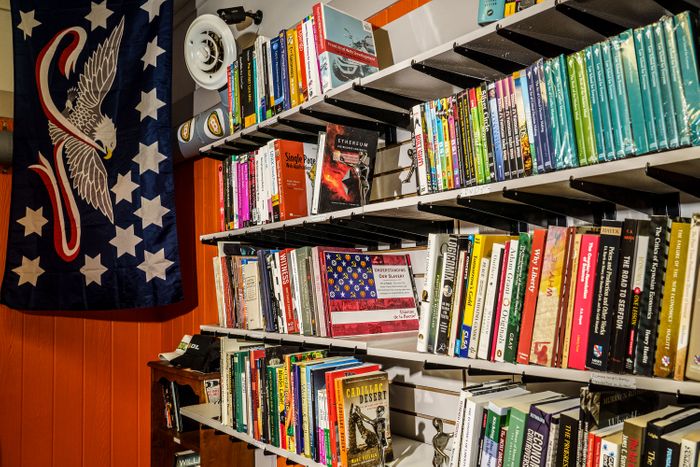

For that, there is probably no better place than Keene. Even at the most innocuous venues, everybody wants to discuss the supremacy of one coin over another or the state-obliterating potential of crypto. (I listened to Freeman’s roommate Matt invoke “total fucking full-scale societal meltdown” outside a bitcoin-accepting Froyo shop.) Aside from Freeman’s home, the other major locus of crypto activity is a cluster on the edge of town. It includes the Mighty Moose Mart, a convenience store; Aria DiMezzo’s home; and a “Bitcoin Embassy,” a carpeted conference room that hosted events and seminars before COVID and now houses an inventory of crypto-themed T-shirts, programming manuals, and books about Austrian School economics. It also kept one of the Shire’s crypto vending machines until it was seized by the FBI. All of this property is owned by the Shire Free Church.

The first time I drive to the complex, I meet the Mighty Moose’s managers, Chris Reitmann and Colleen Fordham (who is one of Freeman’s co-defendants, charged with wire fraud). Soon, a software engineer known as Mr. Penguin walks in to buy a sandwich. Wearing a FREE THE CRYPTO SIX T-shirt, he’s midway through a lecture on a merchant-friendly coin variant called bitcoin cash when Edgington enters in search of jerky. Working the register is Kruse, Freeman’s girlfriend, who is 25 and a Free Stater from San Antonio. Her plan, she says, is to earn money at the Moose while pursuing her calling as a “peace nun” at the Shire Free Church. “I would invite other people to be peace nuns with me, but I wouldn’t want to give them goals,” Kruse says. Edgington, the convicted murderer, pays for his jerky in bitcoin cash.

When Freeman had his bitcoin revelation in 2011, the currency struck him as a kind of cheat code, a way to graduate from local rabble-rousing to hobbling the big state. “The other side of doing exciting activism is people hate you,” he says. “If I could have come here in 2006 and — instead of doing things that people would hate — done things that could help them protect their wealth from government ravages? I mean, that would have been a better way to go about things.”

In 2012, Freeman established the Shire Free Church with four others, including Edgington. Nominally, it formalized the role Freeman played as an activist, blogger, and radio evangelist preaching against government coercion; more practically, he transferred ownership of “Free Talk Live” and his possessions, including his house, to a nonprofit governed by the church’s board. (When I ask if he did all this for the purposes of tax evasion, he tells me that there was no need, as he hasn’t paid federal income taxes since 2004.)

Meanwhile, many “Free Talk Live” sponsors were paying their invoices in cryptocurrency. That crypto then became the possession of the Shire Free Church. “From a peace-church perspective, it dovetailed perfectly with our mission,” Freeman says. “Every dollar that gets out of their system” — meaning the government’s — “is one less dollar they have to go to war with.” Problem was, there was nothing to do with the funds except change them into dollars, which defeated the purpose. To stoke an everyday crypto market for goods and services, Freeman began spreading the bitcoin gospel around New Hampshire, explaining to small merchants what it was and why it could appeal to a state full of anti-authoritarians and goldbugs.

In 2013, he convinced a Keene convenience mart to start accepting crypto; a year later, a Free Keener put a bitcoin vending machine in his thrift store. More terminals followed. A person would deposit dollars and get an equivalent amount of bitcoin virtually, less a fee; the Shire would then repurchase more crypto-currency and restock its inventory. Shirefolk drifted from activism to crypto, with Freeman persuading more and more local businesses — barber, mechanic, pho place — to accept digital payments, giving Keene a claim to the densest concentration of bitcoin activity in the country. Coverage followed in the nascent crypto press, then in mainstream outlets, especially as the price of bitcoin soared, tanked, and soared again.

With the rise of great fortunes came legal scrutiny and high-profile blowups. In October 2013, the FBI arrested Silk Road’s founder. BitInstant collapsed, and hackers looted Mt. Gox. The Winklevoss twins joined others in tacking toward respectability, creating a crypto exchange called Gemini boasting strict compliance with government and industry rules. To some, these developments suggested crypto was growing up. To Freeman, regulation threatened to sap its outlaw vitality. (To Bonnie Kruse as well: “It makes me really sad that Gemini is like that because I’m a Gemini,” she says.)

One of the biggest legal problems bedeviling the new platforms were the “Know Your Customer” safeguards required of mainstream financial institutions. These are meant to discourage, say, terrorists and arms dealers from transacting with impunity. One founding premise of crypto, of course, was to not know your customer, and Freeman resolved to keep proliferating bitcoin on his own terms.

In 2016, using the handle FTL_Ian, he began selling bitcoin on a Craigs-list-style site called localbitcoins.com, executing at least 3,000 transactions with 2,161 partners. Based in Finland, the site seemed to operate in a legal gray area, affording buyers an anonymity not permitted by big, regulated U.S. exchanges like Coinbase. Users paid Freeman for that privilege in transaction fees that were inflated by roughly 10 percent. From a financial perspective, Freeman was doing arbitrage: buying bitcoin on mainstream exchanges for cheap, then selling it in bespoke fashion for more. From a Shire perspective, he frames it in loftier terms. “The whole point of this mission is to give people the opportunity to get out of the dollar,” he says. “The government money is evil, and this money isn’t.” But when I press him on who — besides romance scammers and the like — would pay fees that high, given the better rates on the regulated exchanges, Freeman doesn’t offer a satisfying explanation.

Even at the time, Freeman knew he was in the government’s crosshairs. In 2016, he parted with the Free State Project after making some impolitic comments about federal age-of-consent laws. Then, on the air, he accused the FBI of being the “world’s largest distributor of child porn,” a reference to a case involving a sting site the bureau had set up. Within days, the Feds had a warrant to search Freeman’s house and seize computers to look for contraband images. (Nothing was found, and no charges were filed.) Two years later, FBI agents appeared at the home of Freeman’s ex-girlfriend, asking questions about bitcoin.

The Free Keene ethos is about nothing if not recklessly provoking law enforcement into punishing you and then drawing attention to the state’s aggression. Still, some in the Shire seemed to have gotten spooked by the specter of prosecution. T. J. Cleveland, a mathematics whiz who says he used to work as an NSA analyst, once lived with his husband in Freeman’s house. He says Freeman would suggest to friends that they sell bitcoin to make ends meet — and that when Cleveland told him he would do so only if he could get the proper license, Freeman shrugged off his concerns.

Cleveland lays out for me a simple hypothetical showing how Freeman’s operation could have facilitated crime. “There are con artists out there who will call Granny and say, ‘We’re with the Social Security Administration, and you owe us $10,000.’ Granny says, ‘Oh no, what do I need to do?’ They say, ‘Mail $10,000 to the Shire Free Church.’ ” In the hypothetical, Freeman would receive the money in the mail, unaware of the scam, and release bitcoin to the con men. Cleveland says he conveyed his worries to Freeman. “I said, ‘I don’t know if the FBI is going to go after us one day, but they could.’ ” Eventually, Cleveland and his husband moved out of Freeman’s house — and New Hampshire entirely.

Over time, Freeman seemed less interested in playing it safe. His bank accounts were periodically shut down, and he offered his friends — now his co-defendants — commissions to open accounts on his behalf. Bank accounts proliferated under the conspicuous names of other local “peace churches”: the Reformed Satanic Church, the Church of the Invisible Hand, the Crypto Church of NH. Last year, a cartoonishly narc-y character showed up at a Free Keene party, announcing himself as a liberty-loving car salesman. Later, messaging with Freeman on the encrypted app Telegram, he said he was a heroin dealer looking to buy crypto. Freeman replied that he could not “knowingly” sell to him, as doing so would run afoul of money-laundering laws. He wondered if the man was an undercover agent, but he kept up a friendly banter. “I’m not opposed to your line of work,” he wrote. “Hope you understand. You’re certainly welcome in Keene, of course.” The dealer, court documents strongly suggest, worked for the FBI.

Photo: Mark Peterson/Redux for New York Magazine.

Photo: Mark Peterson/Redux for New York Magazine.

Photo: Mark Peterson/Redux for New York Magazine.

Photo: Mark Peterson/Redux for New York Magazine.

Inside the Bitcoin Embassy and Freeman’s studio. Photo: Mark Peterson/Redux for New York Magazine.

Inside the Bitcoin Embassy and Freeman’s studio. Photo: Mark Peterson/Redux for New York Magazine.

The day after the “Free Talk Live” show about NFTs and slavery, Freeman is in the studio sweeping broken glass that’s still left over from the FBI raid. He sits down across from me with an expectant look on his face, as if I’m just the latest supplicant to arrive at his ministry. “How can I help?” he asks. He’s facing a mandatory minimum sentence of ten years and a maximum of life in prison, but it doesn’t seem to occur to him to refer me to his lawyer or put anything off the record.

The federal indictment against the Crypto Six doesn’t allege that Freeman intentionally worked with scammers. Nor does it allege that he laundered money — only that he didn’t block an FBI agent from using a Shire vending machine. The thrust of the case is that Freeman willfully abetted criminal behavior by looking the other way and lied to banks to keep doing it.

Freeman offers up some rebuttals. His reputation on localbitcoins.com was as a stickler, he notes, and he periodically fielded complaints from users about his requests for minimal ID, such as a photo of a driver’s license. More tenuously, he argues he wasn’t defrauding banks when he told them he was dealing in rare coins. “They are rare coins,” he says, pointing out that only 21 million bitcoins will ever be mined. “That’s the truth. It’s just not saying ‘bitcoin,’ because if you say ‘bitcoin’ to banks, they’ll freak out. They hate that shit.”

In general, though, Freeman doesn’t dispute many facts of the case. “Maybe they wanted me to turn on the machine’s anti-money-laundering requirements or something,” he says, shrugging. At another point, I ask him which cryptocurrency pioneer has most influenced him, and he answers without hesitation: Silk Road’s Ross Ulbricht. This is a dicey thing to say when you are facing federal prison, given that Ulbricht is serving a double life sentence for distributing narcotics. But for Freeman, to abide by a tamed version of crypto was to miss the essence of crypto.

“Please don’t take this out of context and make it the headline of your article, but he’s probably guilty of unlicensed money transmitting,” says Roger Ver when I reach him in Tokyo. “But the very idea that you need to have permission to send money from one human being to another — that’s crazy! Just because something’s illegal doesn’t mean it’s morally wrong.”

Freeman and the other defendants will face intense pressure to take a plea deal before a slated 2022 trial, although if anyone could cherish a kamikaze court battle, it’s them. (“Any Free Stater is going to hang the jury,” Aria DiMezzo reasons.) Freeman’s attorney, Mark Sisti, argues the DOJ has overplayed its hand. “I think they were thinking it was going to lead to something much bigger, connecting to who the hell knows — dark-web crap,” he says.

One person who has managed to stay unindicted is Mark Edgington, whom I meet outside Keene at a combination gas station and deli. At 50, he is in some ways the Shire’s temperamental outlier, with lots of Sarasota still on display: gelled hair, shock-jock voice, golf-dad attire. He says he never got involved with the financial aspect of the mission. “I wasn’t buying and selling cryptocurrency, because I think it’s stupid,” he says.

He’s been in prison and isn’t looking to go back. Even before the charges hit, Edgington had burned out on the Shire. He’d tucked away some early crypto and bought a lake house, and he now lives half the year in the Mariana Islands. “Ian and I have completely different goals on what we want to do with our cryptocurrency,” he says. “I want to create a place that’s actually free, rather than a bunch of recalcitrant, autistic people running around arguing with each other. People have been in New Hampshire for 20 years, and not much has occurred.”

A few months ago, Edgington was served a subpoena to testify before a grand jury; he assumes the Justice Department wants him to flip on Freeman. Perhaps to unburden a guilty conscience, he entertains the idea. “I love Ian, I call him my brother for a reason, and I won’t do anything intentionally that gets him locked up,” he says. At the same time, he acknowledges, “I have the most to gain.” He and Freeman are the last remaining board members on the nonprofit that controls the Shire Free Church — the three others gradually left — which means he would come to control its crypto hoard if Freeman goes away. “If somebody wished to kill the king, it’s usually the one who’s next in line for the throne,” he says. “People end up dead in a river over this kind of money — over a tenth of this kind of money.” Recently, he’s been in Central America, scouting locations for a new venture: an autonomous colony that runs on cryptocurrency, made possible through an obscure tax instrument. The region seems open to moon-shot economic schemes; El Salvador recently announced it would accept bitcoin as legal tender. Wherever he lands, Edgington says, “I’d like to have 100 hectares.”

In June, two cryptopaloozas reflected the split between where bitcoin is going and where it began. One was in Miami, where 12,000 die-hard speculators descended for a debauched conference called Bitcoin 2021. The meme-heavy mood of the weekend captured the performative chaos of decentralized finance, where investors front their bona fides on Twitter with penguin avatars. Jack Dorsey, the Winklevoss twins, and the mayor of Miami were among the headliners. Tickets were reselling for as much as $21,000. A write-up in the New York Times called it the biggest bitcoin conference in the world, “a raging fireball of finance, technology and joyful anarchy, of unfathomable wealth and desperate striving.”

The second took place two weeks later at a grungy site called Roger’s Campground in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. Every year at this time, the Free State Project stages the Porcupine Freedom Festival, a weeklong celebration of libertarian ideals and latent power. (A porcupine flares its quills only when aggressed.) You’ve never seen a nerdier group of people with concealed handguns. “Porcfest” latched on to crypto early: It was here, in 2012, that Ver gave away a stash of collector’s-item physical bitcoins, including the ones the FBI would later seize from Freeman. A year later, a 19-year-old Bitcoin Magazine writer named Vitalik Buterin covered the event; he would soon found ether, the world’s second-most-valuable digital coin, with a market cap of more than one-third of a trillion dollars.

This year, about 2,500 people showed up. For the Porcfest faithful, Freeman’s prosecution isn’t taking place in a vacuum, but amid unprecedented heavy-handedness on the part of the U.S. Establishment, from mask and vaccine mandates to multitrillion-dollar stimulus spending. Naomi Wolf, the feminist author turned vaccine skeptic, was a featured speaker, decrying her cancellation. The disparity between the two events — in attendance, media coverage, glamour, you name it — made it impossible to ignore that the winners of the crypto gold rush can seem like the ones furthest removed from its original vision.

Porcfest’s main space had been christened the Crypto 6 Pavilion, but its ringleader was unable to attend. The terms of his bail keep Freeman at home on Leverett Street as he awaits trial. The last time we speak, he gives me the news from Keene. The court is restricting him from talking to anyone he has traded with in bitcoin, which means many local vendors, and he worries that a restaurant called Local Burger is abandoning its commitment to crypto. But his friends recently threw him a surprise party in his yard, and he tells me he’s happy about that. Then he gets off the phone. “Free Talk Live” is about to begin.

*This article appears in the August 16, 2021, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

See All